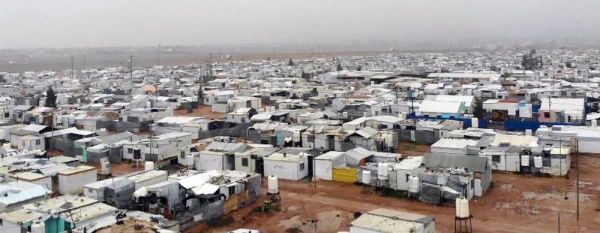

A new Arab Spring? Photo source: The Syrian Observer

Renewed civil war beckons in Syria, unnoticed by the American

news media.

The central bank no longer has US dollars to defend

the Syrian pound, which has plummeted to 15,000 pounds per dollar. Prices are

more than doubling every year, and the pace is accelerating. Well more than 90%

of the population is poor even by the World Bank standard of $2.15 per day (using 2017 prices).

Under the dictatorial President Bashar Assad, Damascus

has responded to the hyperinflation by nearly doubling fuel prices and cutting

back on military salaries. Public salaries have dropped to as little as $7 to

$10 per month, and the government in most of the country is at a standstill. The

only remaining domestic supporters of Assad, the elite, are revolting. Organizing

via Facebook, the students in al-Aswayda Province have shut down the schools. Youth

protests are also mounting in the southern province of Daraa. The Druze lead protests

in certain areas.

Assad long was supported, and instructed in the art of

brutality, by the Russians, who enabled Assad to dominate the civil war that broke

out in the pro-democratic Arab Spring of 2011. The Russians are still bombing

the opposition in the northeast, among more than 450 Russian raids this year,

according to the White Helmets, a Syrian rescue group. But the most effective

Russian forces in Syria were the Wagner group, now in disarray after the

assassinations of their two leaders in a plane crash near Moscow this week. That

leaves Iran as Assad’s only real ally. For weeks he has been edging towards Tehran,

which gives him oil and dollars (the latter through joint banks). Will they insist

on giving him military support as well?

Israel wouldn’t condone an expanded Iranian presence

without a fight. It already bombs Syrian airports with some regularity, interfering

with a few humanitarian routes into the country. So…where are the Americans?

Close to the thick of the fight. The head of Central

Command, General Michael Kurilla, this week visited two major refugee camps in northeast

Syria, an opposition area, to express solidarity and to meet with the 100,000-member

Syrian Democratic Forces, largely Kurdish. Ostensibly, the main American goal

is to thwart Daesh (the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State) by working with the terrorists’ Kurdish foes -- to the

dismay of Turkey, which regards Kurdish nationalists as terrorists itself. Confused

by the complex conflict, and perhaps making a gift of Middle Eastern power to his friend in the Kremlin, former President Donald Trump had ordered withdrawal

from Syria. But he countermanded this command after the military recommended "guarding" the Syrian oilfields in the northeast. "Oil" is the magic word to Trump. Now reportedly the Americans are

quietly organizing opposition to Assad through tribal groups in Syria.

One of two outcomes seems likely. Most probable, I think,

is that Iran will take charge in Damascus. Regional conflict and perhaps regional

war will follow, pitching Iranian Shiites against Sunnis in neighboring

countries like Saudi Arabia. Most of the 19 million Syrians would likely starve

in the resulting neglect.

The other possibility is that Assad will see the light

and work with the Arab League to settle differences with the opposition to the

extent that he can remain in power. This would mean cooperating more genuinely

with the United Nations on humanitarian aid; restoring fuel subsidies and military

salaries; and extending aid to non-opposition Syrians who, according to the UN

humanitarian agency, already cannot afford much food, especially in the wake of

Russian blockage of Ukrainian wheat exports.

These salutary measures would require a credible

dollar reserve at the Syrian central bank, which has bungled monetary policy

for more than a decade; and foreign aid, superficially perhaps through the Arab

League -- but really from Saudi Arabia and even the US and Israel, none of whom

want to see Iran become the major player in the Middle East. – Leon Taylor,

Baltimore tayloralmaty@gmail.com

Notes

I thank Nick Baigent, Annabel Benson, Mark Kennet, and Forest Weld for helpful comments.

References

The Syrian Observer.

Various

issues. Main - The Syrian Observer

The Syria Report.

Various issues. Syria Report – Economy, Business and Finance –

Syria and the Middle East (syria-report.com)