KIMEP's Chan Young Bang: Macro or snake oil?

Photo source: The Org

The forced resignation a month ago of the president of Harvard University, Claudine Gay, a plagiarist, reminds us that the gales of politics pervade the groves of academe. And not only in Cambridge. The politicization of the search for truth can be severe in poor countries and transition economies.

A glaring example is Kazakhstan. The president of a Western-style

university in Almaty, Chan Young Bang, became Economic Adviser to the first

president of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, as well as vice chairman of

Nazarbayev’s Expert Committee, which Nazarbayev chaired, in 1990. Three

years later, Kazakhstan went into a hyperinflation of thousands of percent annually.

Nazarbayev was ousted in the deadly riots of January

2022, which were spurred by the government’s sharp and sudden increase of fuel

prices. He was replaced by his erstwhile protégé, Kassim-Jomart Tokayev.

Bang would love to become an economic aide to Tokayev. So he

presents himself as an expert macroeconomist who knows how to boost

Kazakhstan’s rate of economic growth, from 4.5% to 7% per year. But Bang has

never published a paper in a decent refereed journal of economics. In 2020,

Palgrave Macmillan published his book, Transition beyond denuclearisation: A

bold challenge for Kim Jong Un. But

it was heavily rewritten by others, including me, a fact that the book does not

mention. His only academic credential as a macroeconomist is that he is the

principal investigator for the DPRK Strategic Research Center at KIMEP

University, where Bang is President. He was named principal investigator, at his own request,

by a board of KIMEP trustees whom he appointed.

He created the center himself.

Our expert macroeconomist wants to immediately boost

Kazakhstan’s growth rate by more than half through the magic of the multiplier.

This refers to an endless sequence of ever-diminishing amounts of spending that

add up to a tidy sum. I spend $1 at the grocer, who saves 20 cents and spends

80 cents at the pleasure palace. After only two rounds of spending, we have

generated $1.80. Another 64 cents is generated in the third round, and so

forth. In this story, the amount spent from each additional dollar, the marginal

propensity to consume, is 80 cents.

Bang thinks that every industry has a multiplier and a

marginal propensity to consume. By allocating funds across the industries with

the highest multipliers and marginal propensities to consume, the government

can achieve any growth rate it wants.

Rubbish. Bang hasn’t the foggiest idea of what a

multiplier is, or of what constitutes macroeconomics.

The multiplier, and the marginal propensity to

consume, apply to all consumers in a national economy. The idea is that they

all feel confident enough of the economy’s future to keep spending at their

usual rate. If someone fears for the future, she will save rather than spend,

and the sequence of spending will lose a link. Th success of the multiplier in

generating a lot of income rests on the public’s confidence that the government

will avert recession. The charm of a President like Franklin Roosevelt may be

critical to such Keynesian economics, named after the English economist John

Maynard Keynes who proposed that the government encourage people to spend their

way out of the Great Depression.

To believe that the government will avert recession is

not necessarily logical. An opposing assumption in macroeconomics is that

people act rationally in their own interest. The notion of rational

expectations discounts Presidential charm and focuses on the facts. In this

story, people will often have occasion to

save. The multiplier does not play the same powerful role in rational

expectations as in Keynesian economics.

Bang confuses the multiplier with the rate of

return. Suppose that you spend $100

million building a computer platform that generates $120 million in revenues.

Your rate of return is a $20 million profit on a cost of $100 million, or 20%.

The rate of return varies across industries, depending on such factors as

market demand and the productivity and abundance of inputs. If the government

has $100 million to spend throughout the economy, and if it is sure that there

is enough capacity to absorb this much spending, then it would make sense to

allocate the money to the industries with the highest rates of return. But there is

no guarantee that the government can target any growth rate it wants. It must have the needed inputs – labor,

physical capital, and production know-how called technology.

Bang’s list of “key investment-target industries” was

“1. real estate

2. agricultural

3. tourism

4. education

5. IT Technology

6. financial industry.”

The list does not include the industry that dominates Kazakhstan,

oil and natural gas. Over the long run, oil and gas exports account for a

fourth of Kazakhstan’s GDP.

Bang strong-armed the economists at KIMEP into backing

his project, demanding estimates in two days that normally would take months.

To get him off their backs, they proposed “multipliers” to sectors that he

regards as promising industries, such as infrastructure and electronic

products. It would make better sense to think of infrastructure as a form of

physical capital in all industries, but never mind. The point is that the

estimates were proposed more to mollify Bang than to satisfy rigorous standards

of accuracy. And they were rates of return, not multipliers.

Below is the table of “multipliers” that KIMEP’s economists proposed, with a rationale:

“Since

government investment is subject to budget deficit, the multiplier should be

lower than that for private investment, and assume it to be 2. In contrast, the

constraint of investment is likely to be relaxed for the case of foreign

investment and investment made from the national sovereign fund. Therefore, we

assigned the multiplier for these investments to be 4, adding more points from

the general case."

|

Multiplier |

Investment (billion $) |

Impact on economy with multiplier effects (billion $) |

|

|

Private |

3.3 |

0.87 |

3.3 * 0.87 = 2.87 |

|

Government |

2 |

0.30 |

2.0 * 0.30 = 0.60 |

|

Sovereign Fund |

4 |

0.30 |

4.0 * 0.30 = 1.20 |

|

Foreign |

4 |

0.60 |

4.0 * 0.60 = 2.40 |

|

Total |

2.07 |

7.07 |

The

proffered justification of a low fiscal multiplier is obviously wrong. That the

government would spend without constraint suggests that its multiplier is larger,

not smaller, because no tax payments are deduced from the spending. Never mind.

The key point is that the whole table is nonsense. A rate of return is not a multiplier.

To make matters worse, the government does not have a rate of return in the conventional sense, since it is not out to make a profit. As it happens, the fiscal multiplier for Kazakhstan may be about 4.8. See the appendix below for calculations.

In short, the table is incoherent. But, not to worry: An economist at KIMEP writes that Bang “was happy with the numbers for investment amounts, and the suggested distribution of these additional investments into the seven key target-industries.” Another gushes: "This is great news!" Accuracy? Who cares?

In pursuit of a political career, Bang is betting KIMEP’s reputation on a ludicrous proposal.

This story does have a moral. The deans and central

administrators at KIMEP should have set Bang straight, but they feared for

their jobs. Neither have the university trustees (appointed by Bang), or the

Kazakhstan Ministry of Education and Science, objected vigorously to Bang’s

politicization of the academe. The most likely agent to stop politicization is

the faculty, because its mission is to discover and disseminate ideas and facts

– the “truth,” if you will. But in this case, the profs were more interested in

protecting their jobs, and understandably so. The episode does not attest to high academic integrity.

In general, the case exists for establishing a faculty panel or

senate at a university in its check and balance system, and to insist upon the faculty's freedom of academic speech. Otherwise, there is an incentive for a man (or woman) on the make to harness the university's reputation to political purposes, thereby destroying it. – Leon Taylor,

Baltimore tayloralmaty@gmail.com

Notes

The total spending generated by the multiplier from $1

when the marginal propensity to consume is c is

S = $1 + c*$1 + c^2*$1 +… +

To find the multiplier, rewrite this geometric series:

cS = c$1 + c^2*$1 + … +

if c is less than 1, then its power terms will

eventually go to zero. The geometric series thus has a finite total.

Subtracting the second series from the first,

S – cS = $1 - c$1 + c$1 - c^2 $1 + c^2 $1 - ... = $1

Thus S = 1/(1 – c). The multiplier for $1 can be

written as 1/(1-c), if we include the original dollar. In the example of this

article, the multiplier is 5.

Appendix

Denote GDP as

Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where

C = a + b*(Y – T)

M = c + d*(Y – T)

Y = GDP

I = investment

G = government

X = export

M = imports

and

T = taxes

where all terms are real.

Solving,

Y = [a + I + G + X – (b+d)T]/(1 – b – d)

The government multiplier is

dY/dG = 1 / (1 – b – d)

|

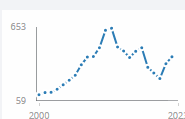

The regression below uses annual data from 1990 through 2022 to estimate the consumption function for Kazakhstan in 2015 international dollars (that is, with adjustments for inflation and exchange rate changes). The marginal propensity to consume is .645. |

||||||

|

Regression Statistics |

||||||

|

Multiple R |

0.976 |

|||||

|

R Square |

0.953 |

|||||

|

Adjusted R Square |

0.951 |

|||||

|

Standard Error |

8182465472.708 |

|||||

|

Observations |

33 |

|||||

|

ANOVA |

||||||

|

|

df |

SS |

MS |

F |

Significance F |

|

|

Regression |

1 |

4.2E+22 |

4.2E+22 |

626.679 |

3.98E-22 |

|

|

Residual |

31 |

2.08E+21 |

6.7E+19 |

|||

|

Total |

32 |

4.4E+22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coefficients |

Standard Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

|

Intercept |

-1349964245 |

3.56E+09 |

-0.37895 |

0.707308 |

-8.6E+09 |

5.92E+09 |

|

GDP |

0.644902953 |

0.025762 |

25.03356 |

3.98E-22 |

0.592362 |

0.697444 |

|

Regression Statistics |

||||||

|

Multiple

R |

0.630014 |

|||||

|

R

Square |

0.396918 |

|||||

|

Adjusted

R Square |

0.377464 |

|||||

|

Standard

Error |

1.04E+10 |

|||||

|

Observations |

33 |

|||||

|

ANOVA |

||||||

|

|

df |

SS |

MS |

F |

Significance F |

|

|

Regression |

1 |

2.22E+21 |

2.22E+21 |

20.40265 |

8.53E-05 |

|

|

Residual |

31 |

3.37E+21 |

1.09E+20 |

|||

|

Total |

32 |

5.59E+21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coefficients |

Standard Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

|

Intercept |

1.93E+10 |

4.54E+09 |

4.242744 |

0.000185 |

1E+10 |

2.85E+10 |

|

GDP |

0.148334 |

0.03284 |

4.516929 |

8.53E-05 |

0.081357 |

0.215311 |

With these two estimates of marginal propensities, we can calculate the government multiplier as 1 / (1 - .645 - .148) = 4.8.