The February 6 earthquakes, up to 7.8 on the Richter scale, killed more than 40,000 in Turkey and left an estimated two million homeless in a population of 85 million, or 2.2% of the population. An aftershock two days ago of 6.3 magnitude hit Hatay province in southern Turkey near Syria. And now for the hard part.

The scramble for scarce food and housing will send prices skyrocketing. Annualized consumer inflation in January 2023 was already 58% (and had been above 80% in November). The domestic producer price index, which measures output costs and thus predicts consumer inflation, was 158%. That's the general picture of prices. Now let's look at shelter and food.

Housing prices were rising swiftly well before the earthquake, by more than 230% from July 2021 to last December, according to the Central Bank of Turkey. Growth in food output has never kept consistently abreast with population growth: The typical Turk is not necessarily getting more to eat over time from local farmers, and actually got less in 2020, as Figure 5 shows. This lack of abundant food sets the stage for rising food prices.

Now, with the earthquakes pushing up demand for shelter and food, rates of consumer inflation exceeding 100% seem hard to avoid. The hyperinflation may decimate the savings of survivors, leaving many too poor to eat.

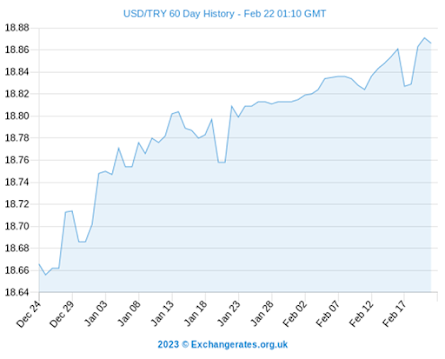

At the heart of the problem is the wobbly Turkish lira. As Figures 1 and 2 below show, the rate of exchange of lira per dollar was rising steadily even before the earthquakes—from the beginning of 2022, in fact. (The sharp revaluation in December 2021 was probably due to Turkey's sensible new policy of protecting lira deposits against depreciation in dollars. The central bank meant this innovation to counter Erdogan's policy of low interest rates, which had caused the lira to lose fans, and thus value, throughout 2021, as Figure 1 shows.)

Since the earthquakes, the lira has become much weaker, as Figure 3 shows. This devaluation pushes up import prices (since it now takes more lira than before to buy a dollar’s worth of goods) and threatens to drain the country’s reserves of dollars (since people will prefer to hold dollars rather than lira). Foreign currency reserves already are dropping fast—11% from December to January, according to the Central Bank of Turkey. Now they seem too low to cover even regular imports, which have been rising sharply since October (see Figure 4) -- much less emergency imports. In January 2023, foreign currency reserves were $67.2 billion, not enough to cover three months of imports at the 2022 rate.

Cash crash

Scary enough. But in truth, Turkey has less cash on hand than this. Any country must pay its creditors first if it wants to protect its reputation and thus borrow in comfort later. (Hello, Argentina.) On one-year loans and such requiring dollars and gold, Turkey's debt in January rose 3.7% in one month to $32.6 billion. As of February 10, right after the earthquakes, it had increased to $34.4 billion. On longer-term trades in financial values, called "derivatives," Turkey's debt maturing in a month is $37.4 billion. In short, Turkey's short-run debt is growing even apart from the earthquakes. Not many dollars may remain for buying food and medicine from abroad. (By "dollars," I really mean foreign exchange, including euros and yen. But for Turkey, it's mainly dollars.)

Turkey has $50.6 billion in gold that in principal could pay for nearly two more months of imports. But one hesitates to dump the sacred stuff at a forced price. And Turkey is obliged to set aside a certain amount of gold in reserves, and to use gold to settle certain debts from derivatives.

On top of it all, Turkey has an eye-popping foreign debt of $2 trillion, which would take nearly two and a half years to pay off if Turkey devoted all its income to it (roughly, gross domestic product, the value of output). And Turkey was scrambling for dollars well below the earthquakes, turning to the Russians for help. With friends like that.... So investors have lots of reasons to dump the lira.

Figure 1: Exchange rates since the beginning of 2021

Source: Central Bank of Turkey

Figure 2: Exchange rates since October

Source: Central Bank of Turkey

Figure 3: Exchange rates in recent weeks

Source: US Dollar (USD) to Turkish Lira (TRY) exchange rate history (exchangerates.org.uk)

Source: Central Bank of Turkey

Humanitarian aid is trickling in. The United States has pledged $85 million. But even if all this aid goes into housing,

it would provide less than $43 per homeless person. NATO is helping, including with tens of thousands of tents. But the estimates of a business group of total economic damages from the

earthquakes run up to $84 billion, or more than 1% of GDP. This would be

125% of foreign currency reserves.

Murk accompanies the gloom, manifest in the "Net Errors and Omissions" account of the international balance of payments, which reconciles unexplained differences between spending and investment. In 2021, the accountants raised the account by $194 million, said the central bank. This year? A cool $1.4 billion, more than 1% of GDP.

If Turkey can get through 2023, the new year may look brighter. It has been down this road before. In 1999, an earthquake of 7.9 on the Richter scale killed 17,000. But the economy in the next year rebounded 1.5% thanks to rebuilding. "The boost to output from reconstruction activities may largely offset the negative impact of the disruption to economic activity," the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) said about this year’s earthquakes. But Erdogan must find dollars to pay builders. And his wacky policy of holding down interest rates, allegedly to restrain inflation when in reality it does the opposite, has put off foreign investors. Portfolio investment fell 2.2% over 2022, according to the Central Bank of Turkey. In this year of recovery from the 2020 pandemic, investment should have risen.

The Turkish story is fluid, and my predictions are merely educated guesses, sans the education. But it is hard to avoid the sense of a looming disaster. –Leon Taylor, Baltimore tayloralmaty@gmail.com

Note

This update corrects Figure 1 to show exchange rates rather than imports. I thank Forest Weld for catching my error. The update also corrects an error about the 2021 adjustment of the "Net errors and omissions" account.

References

Central Bank of Turkey. Konut Fiyat Endeksi (Housing price index). December 2022. Konut Fiyat Endeksi (tcmb.gov.tr)

Central Bank of Turkey. Statistics.

tcmb.gov.tr

Central Bank of Turkey. Uluslararasi Rezervler ve Doviz Likiditesi (International reserves and foreign exchange liquidity). February 10, 2023. RT20230210TR.pdf (tcmb.gov.tr)

France 24. Earthquake sends tremors through Turkey's fragile economy. February 19, 2023. The source of the quote from the EBRD. Earthquake sends tremors through Turkey's fragile economy (france24.com)

Reuters. Turkey extends FX-protected lira deposit scheme for a year. December 17, 2021. Turkey extends FX-protected lira deposit scheme for a year | Reuters

Sune Rasmussen. NATO pledges earthquake aid to Turkey. The Wall Street Journal. February 16, 2023. NATO Pledges Earthquake Aid to Turkey - WSJ

World Bank. World Development Indicators. worldbank.org

I don't quite understand about reconciling differences between spending and investment -- could you explain that more? From those words, it sounds like the concept is that in an ideal world spending would equal investment? But that doesn't make sense to me, so I think I'm misunderstanding something.

ReplyDeleteGood question. To oversimplify (always a good thing in finance), in the international accounts, we can represent every transaction in two ways: As spending, and as investment. I buy a book from a bookstore in Ankara for $10. That's spending (a good imported from Turkey). The bookstore has no use for 10 dollars, because you need lira in Turkey to buy things. So the bookstore will put the dollars in a dollar asset to earn a return. For example, it may buy a dollar savings account (an asset exported from Turkey). That's investment. Even if the bookstore just hangs on to the dollars, that amounts to investing in cash. Here's another way to think about it: Every international purchase of a good is tied to a sale of an asset, because the money spent on the good is an asset to the seller, who must invest it to profit from it.

DeleteI see. Thanks!

Delete