Shopping in the Panchshanbe bazaar of Tajikistan. Photo: Alamy

Tajikistan is the most instable country in an instable

region. It is still smarting from a

civil war that killed tens of thousands in the mid-Nineties, amid the chaotic

transition to independence and markets from the Soviet era. Figure 2 shows that

Tajikistani income halved in three years, from 1993 to 1996, when measured in a

way that adjusts for changes in prices and exchange rates.

Remarkably, income has risen steadily ever since, as

Figure 2 shows. The global fiscal crisis of 2008 and the pandemic of 2020,

barely had visible effects, perhaps because Tajikistan lacks a modern finance

sector and is isolated by geography from the rest of the world. Tajikistan’s economy has even become slightly

larger than that of Kyrgyzstan, its northern neighbor prone to small civil

wars.

Despite this progress, Tajikistanis have a nagging,

puzzling problem. They spend little of the little that they earn.

Over the long run, of another international dollar,

they spend only a fifth, as Table 1 shows. They save the rest, either

voluntarily or as taxes (which are forced savings). To some extent, this

reluctance to spend may reflect an unusual sample of data, always a danger when

you’re dealing with Tajikistani records. But as Table 1 also shows, in

virtually any sample, the marginal propensity to spend is very likely to be

low, ranging from 18 cents to 23 cents on the international dollar.

In contrast, Americans spend more than four-fifths of

another international dollar. Russians are similar. Even in Central Asia, where

households spend prudently, Kazakhstanis spent two-thirds of another

international dollar. (An international dollar is an artificial currency that

buys the same amount of, say, a burger, anywhere around the world.) Tajikistanis are surprisingly frugal.

They need to spend, for they are poor. The income of

an average Tajikistani is only one-sixteenth that of an American. In 2022, it was 4,137 versus 64,703 in 2017

international dollars. What gives?

One possibility is that life is cheap in Tajikistan.

Unskilled workers so abound that many go to Russia to work – 93% of the 720,000

who worked abroad in 2008, reported the International Labour Office. Their

earnings were nearly half of Tajikistan’s total income in 2008. This excess

supply of labor drives down wages and thus prices in Tajikistan.

Yes, life in Tajikistan is cheap – but leaves much to

be desired. In 2021, the typical Tajikistani at birth could expect to live 71.6

years, as compared to 76.3 years in the US and 79.9 years in high-income countries

in general. (The American record in life expectancy is a disgrace but fodder

for another post.)

Another possibility is that Tajikistanis, having

suffered an economic revolution and the most severe civil war in the region, so

fear the future that they save for a very stormy day. They don’t save most of

their income because they lack things to spend. They save because they fear

that someday they will have no income to spend. Their porous southern boundary

with Afghanistan, a revolving door for terrorists, may reinforce this fear.

A final possibility is that Dushanbe taxes away too

much income for them to have much left to spend. The question is how much money

a Tajikistani thinks that she needs to set aside for future taxes. This

expectation, in turn, may hinge on the trend in the share of public debt in

GDP.

Statistics for this are spotty in the World

Development Indicators. The only data for Tajikistan are for 2000 and 2001,

114% and 80%. These are very high numbers. For example, the counterpart figure for

Colombia in 2022 was only 70%. But one cannot use 23-year-old data as a

reliable guide to expectations formed today.

More data exist on the GDP share of government

expenses – basically operating costs, which include salaries. Tajikistan’s

figure in 2021 was 12.5%, far below the world average of 32% (!). Of course,

this does not include capital spending on dams and other construction projects,

which is important in Tajikistan. But overall the skimpy data provide no reason

to think that Tajikistanis save most of their income because they fear high and

rising taxes. As a share of GDP, tax revenues rose from 7.7% in 1998 to about 10% in 2004. As of 2021, it was still 10.3%. Yes, these are low tax shares by global standards; the world average exceeds 15%. But they are in line with tax shares elsewhere in Central Asia. And they certainly do not follow a pattern of falling taxes that would presage an inevitable hike for which Tajikistanis should start to save today.

Both tables indicate that at a hypothetical income of zero, Tajikistanis consume in both the short and long run. They may borrow from future taxpayers through a government deficit. Or they may consume out of foreign aid and gifts.

Both tables also suggest that Tajikistanis spend less of the additional dollar in the short run than in the long run, perhaps because they learn over time how to buy durable goods, like autos, that they can postpone. The marginal propensity to consume is .11 in the short run and .2 in the long run.

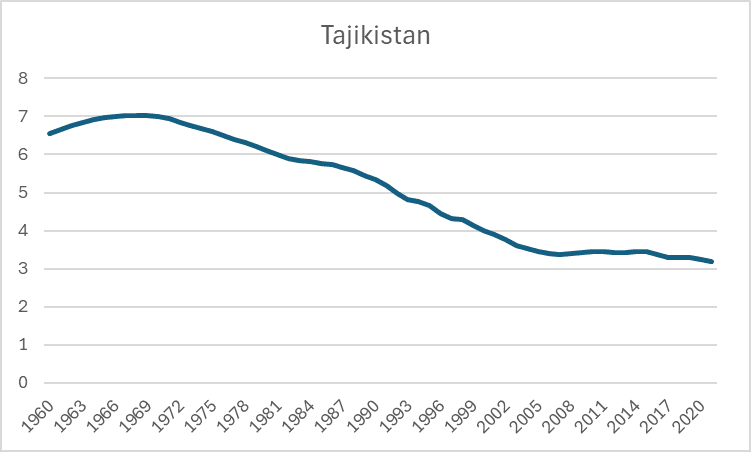

A final possibility is that Tajikistanis are saving for large families. But in fact, the fertility rate has halved in 40 years; see Figure 6. Families are becoming smaller, so they can't explain why Tajikistanis save so much, unless the cost of family living is growing even faster than families are shrinking.

The most likely explanation for the Tajikistani

reluctance to spend is political uncertainty. There is growing speculation that President Emomali Rahmon will step aside in favor of his son, although he did run for a fifth term in 2020. The next election is in about 2028. The uncertainty does not bode well

for an authoritarian government that has been in power

since shortly after the nation became independent in 1992. Misery loves

saving, but people don’t love misery. –Leon Taylor, Baltimore tayloralmaty@gmail.com

Table 1: Long-run consumption function for Tajikistan, 1993-2021

|

Adjusted

R Square |

0.902 |

|||||

|

Standard

Error |

6.16E+08 |

|||||

|

Observations |

29 |

|||||

|

ANOVA |

||||||

|

|

Df |

SS |

MS |

F |

Significance F |

|

|

Regression |

1 |

9.86E+19 |

9.86E+19 |

259.556 |

00.0 |

|

|

Residual |

27 |

1.03E+19 |

3.8E+17 |

|||

|

Total |

28 |

1.09E+20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coefficients |

Standard Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

|

Intercept |

2.51E+09 |

2.46E+08 |

10.207 |

9.14E-11 |

2E+09 |

3.01E+09 |

|

GDP |

0.201 |

0.012 |

16.111 |

2.26E-15 |

0.175 |

0.226 |

Table 2: Short-run consumption functions

for Tajikistan, 1993-2021

|

Adjusted

R Square |

0.922 |

|||||

|

Standard

Error |

5.5E+08 |

|||||

|

Observations |

29 |

|||||

|

ANOVA |

||||||

|

|

df |

SS |

MS |

F |

Significance F |

|

|

Regression |

2 |

1.01E+20 |

5.05E+19 |

166.845 |

00.0 |

|

|

Residual |

26 |

7.87E+18 |

3.03E+17 |

|||

|

Total |

28 |

1.09E+20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coefficients |

Standard Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

|

Intercept |

2.51E+09 |

2.19E+08 |

11.44 |

0.00 |

2.06E+09 |

2.96E+09 |

|

GDP |

0.111 |

0.034 |

3.29 |

0.003 |

0.042 |

0.180 |

|

Time |

1.04E+08 |

37060585 |

2.81 |

0.009 |

27926480 |

1.8E+08 |

Figure 1: Consumption /GDP ratio for Tajikistan,

1993-2021

Figure 2: Tajikistan GDP, 1993-2021

Figure 3: GDP of Central Asian countries, 2021

Figure 4: GDP of Russia and Central Asian countries,

2021

Figure 5: GDP in Russia and Central Asia, 2021

Figure 6: Fertility rate in Tajikistan, 1960-2021

Notes

All data are from the World Bank’s World Development

Indicators.

The data in the tables are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for 1993 through 2022. GDP is gross domestic product. Time gives the number of years that have passed since 1990, where Time = 1 for 1990. Consumption is personal consumption expenditures. GDP and Consumption are expressed in 2017 and 2015 international dollars, using purchasing power parity.

References

International Labour Organization. Migrant remittances to Tajikistan: The potential for savings, economic investment and existing financial products to attract remittance. obl-eng.p65 (ilo.org) 2010.

Catherine Putz. Tajik President Emomali Rahmon to Seek Fifth Term – The Diplomat. August 27, 2020

World Bank. World Development Indicators. worldbank.org

No comments:

Post a Comment