Chinese shoppers, look for the blue-light special. Photo: CTGN

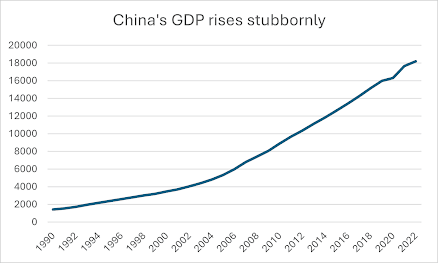

In a few decades, China rose from the ranks of the

poorest to the affluent. Its economy burgeoned ninefold from 1990 to 2022 (see

Figure 1). One reason for this economic miracle is that the Chinese save like

prophets. Firms and governments borrow

these abundant funds to build roads, dams, and factories. This expands China’s

capacity to produce and thus its income. China adds far more value in

manufacturing, as a share of its economy, than the typical country; see Figure

2.

Adjusting for inflation and changes in exchange rates,

China has been the world’s largest economy since 2014. Yes, I know that you hear from the news media

that the US is still the largest economy. American reporters are economic

illiterates, led astray by fluctuations in the exchange rate of renminbi per

dollar. These fluctuations have more to

do with temporary rises and falls in money supply than with an economy’s long-run

ability to produce.

Figure 1. China’s gross domestic product, 1990-2022,

in 2017 international dollars.

Figure 2. Manufacturing value added, as a share of

GDP, in China and the world, 2004-2021.

Just how much does China save? Over the long run, the

typical Chinese spends just 55 cents of every international dollar earned; see

Table 1. She saves the other 45 cents, either voluntarily or as tax payments,

which are forced savings. In contrast, Americans spend more than four-fifths of

an additional international dollar. You

would think that since Americans are richer than Chinese, they would save more

of another dollar, because they have already met their essential needs. But

that’s not the case. The Chinese save even more than Kazakhstanis.

(An “international dollar” is an artificial currency

that expresses the cost everywhere of buying a good that would cost a dollar in

the United States. By controlling for changes in the exchange rate, it

expresses the same purchasing power everywhere. We thus avoid the mistake of

thinking that an economy has grown in productive capacity merely because its exchange

rate has strengthened for a few months.)

Table 1. China’s long-run consumption function, 1995-2022

|

R

Square |

1.000 |

|||||

|

Adjusted

R Square |

1.000 |

|||||

|

Standard

Error |

1E+11 |

|||||

|

Observations |

28 |

|||||

|

ANOVA |

||||||

|

|

Df |

SS |

MS |

F |

Significance F |

|

|

Regression |

1 |

1.81E+26 |

1.81E+26 |

17956.18 |

0.00 |

|

|

Residual |

26 |

2.62E+23 |

1.01E+22 |

|||

|

Total |

27 |

1.81E+26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coefficients |

Standard Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

|

Intercept |

-6.6E+10 |

3.61E+10 |

-1.84 |

0.078 |

-1.4E+11 |

7.9E+09 |

|

GDP |

0.547 |

0.004 |

134.0007 |

1.87E-38 |

0.539 |

0.555 |

Why do the Chinese save so much? Asians in general

save in spades, but that hound don’t really hunt. It explains nothing.

Maybe couples must save to raise those famously large

families. In the 1960s, a Chinese woman

averaged more than seven births. That

was almost triple the number needed to keep the population from declining; see

Figure 3.

But the fertility rate has been falling for decades. This is thanks largely to China’s draconian

policy in the 1970s to allow a couple to raise only one child, to defuse the

then-dreaded Population Bomb. China today might like to have that Bomb back.

Its population has just stabilized at 1.4 billion, and forecasts say it will

even shrink; see Figure 4. In any event, Chinese families are getting smaller,

so they don’t need bigger nest eggs.

Figure 3. The fertility rate in China, 1960-2021.

Figure 4. China’s population, 1960-2022.

Again: Why do the Chinese save? Maybe it’s to pay the taxes of a government that has been a Leviathan for centuries. People have gotten into the (forced) habit of saving for the rainy day, in a country where the government seems to rain every day. But even this explanation falls short, because China has been taxing lightly for at least two decades. The ratio of tax revenues to GDP is only about 8%; see Figure 5. The world average is almost double that. So why haven’t the Chinese loosened their belts in response to softer taxes? Maybe spending habits are hard to change. Which, of course, just begs the question.

Figure 5. Share of tax revenues in GDP, 2005-2021.

In the short run – up to a year – the Chinese spend slightly more of an international dollar than in the long run, probably out of necessity; see Table 2. But over time, they cut spending by 23 billion international dollars, when controlling for income. The Chinese indeed have a passion to save.

Table 2. Short-run

marginal propensity to consume in China, 1995-2022

|

R

Square |

1.00 |

|||||

|

Adjusted

R Square |

1.00 |

|||||

|

Standard

Error |

9.51E+10 |

|||||

|

Observations |

28 |

|||||

|

ANOVA |

||||||

|

|

df |

SS |

MS |

F |

Significance F |

|

|

Regression |

2 |

1.81E+26 |

9.03E+25 |

9985.716 |

0.00 |

|

|

Residual |

25 |

2.26E+23 |

9.05E+21 |

|||

|

Total |

27 |

1.81E+26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coefficients |

Standard Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

|

Intercept |

-2.8E+10 |

3.93E+10 |

-0.716 |

0.481 |

-1.1E+11 |

5.28E+10 |

|

GDP |

0.586 |

0.020 |

28.982 |

0.00 |

0.545 |

0.628 |

|

Time |

-2.3E+10 |

1.16E+10 |

-1.978 |

0.059 |

-4.7E+10 |

9.48E+08 |

This is not always fortuitous. Central Asia would

certainly prefer that the Chinese buy more imports. And the Chinese themselves

may suffer from their frugality. For when the world economy slows, the Chinese

must provide their own fuel to crank up their GDP engine. If they balk at spending,

recovery may slow. In fact, at a hypothetical income of zero, there is no

evidence that the Chinese would spend anything (see Table 2), even though they could

probably borrow from future taxpayers by selling bonds to be paid off by hiking

future taxes. The Chinese puzzle lives on. – Leon Taylor, Baltimore, tayloralmaty@gmail.com

Notes

For useful comments, I thank but do not implicate

Annabel Benson and Mark Kennet. All data are from the World Development Indicators of the World

Bank, worldbank.org

The data in the tables are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for 1993 through 2022. GDP is gross domestic product. Time gives the number of years that have passed since 1990, where Time = 1 for 1990. Consumption is personal consumption expenditures. GDP and Consumption are expressed in 2017 and 2015 international dollars, using purchasing power parity.

No comments:

Post a Comment