Meet KIMEP's new dean. Credit: Getty Images

A few months ago, in one of his periodic blowups, as predictable as thunderstorms in summer, the President of KIMEP University, Chang Young Bang, fired the longtime dean of the College of Social Studies, Gerald Pech. Since then, the university has scrambled for Pech’s successor. It seems to have found him, and I must say that Dr. Bang richly deserves him.

KIMEP flew in Jason Gainous, last seen at Duke Kunshan

University (search me), to present a Powerpoint seminar entitled, “Interconnectedness

and impact: Leading the future of social sciences.” It went downhill from there. Dr. Gainous is passionately concerned with “the

web of interconnectedness,” in which “social sciences are increasingly interconnected,”

“human behaviors and societal structures are interwoven, influencing global

phenomena (hey, they’re interconnected, too!), and “digital technologies are

reshaping disciplinary interconnectedness.” And that was just the first slide.

But listen, we’ve got to get our priorities straight, because “interconnectedness

fuels impactful changes beyond social sciences.” Dr. Gainous’s inspiring vision

embraces “Unified Impact: Merging Liberal Arts with Social Sciences.” This

breathtaking dream focuses on “philosophical interconnectedness” with “holistic

insights” that “deepens [sic] understanding of human and societal dynamics.” I

don’t know about you, but my pulse is already racing, especially since Dr.

Gainous is dedicated to “Building Interconnectedness Through a New Political

Science Department.”

But enough of the noble nightmare, er, dream. Let’s

get down to brass tacks! Dr. Gainous proposes the KIMEP Center for Social

Science Research Methods. This would develop a “comprehensive Ph.D. program focused on

advanced research methods (I guess we wouldn’t want a doctorate focused on

backward methods), including applied statistics, modeling, artificial intelligence,

big data, and machine coding, and qualitative methods.” Research Methods

Training Seminars would “foster[] a community of learning and sharing, interconnectedness

(of course!) and impact.”

Most of Dr. Gainous’s gas production can be safely

dispersed. But his new Ph.D. program is

another matter, because it must be approved by the Ministry of Education and

Sciences. So let’s talk about it.

Dr. Gainous is a connoisseur of ritzy-sounding terms

that he doesn’t understand. “Applied statistics” is “modeling.” On the other

hand, AI, big data and coding, and qualitative methods are very separate

concepts.

Qualitative methods are as old as statistics

themselves. We can measure data in two ways. One is in small chunks. For

example, we can measure income in dollars and cents. But not all data are

suitable for continuous numbers. An example is gender. It’s male or female, and

it cannot be measured with a number. Another example is racial origin. Such data

are “qualitative.” Data that can be measured are “quantitative.”

Nothing about qualitative data requires a new

doctorate degree. It differs from quantitative data only in its units of

measurement. We can gauge the impact of a one-dollar increase in income on

spending. Those data are quantitative. But if we’d like to know how gender

affects spending, we will have to compare spending by a male to spending by a female.

The usual way to do this in a statistical model is with a variable that has the

value of 1 for females and 0 for males. For example, suppose that we estimate this

model: Spending = 40 + 2* Female. The typical female spends 40 + 2*1 = 42. The

typical male spends 40 + 2*0 = 40. That’s all there is to it.

Well, almost all. There is a temptation to introduce two

gender variables, Male and Female. Male would equal 1 for males and 0 for

females. Female would equal 1 for females and 0 for males. But a moment’s

thought will show that this is saying the same thing twice. If we have a Female

variable, we already have a distinctive value for males; it’s Female = 0. We do

not need a Male variable.

In fact, if we include both Male and Female variables,

the statistical software may go berserk. This is because it assumes that all

data in a dataset are useful. The Male

variable is useless, because it duplicates what we already know from the Female

variable. But as long as we avoid such duplicate variables, we will have no problem

with qualitative data. That part of Dr. Gainous’s “advanced” doctorate can be

explained in five minutes.

“Big data” is another term for which Dr. Gainous needs

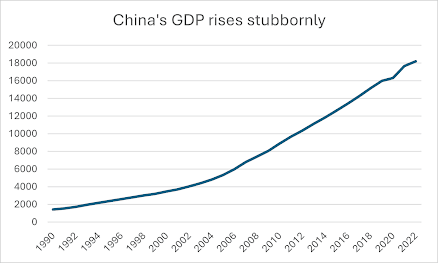

to go get a clue. It just refers to a lot of data. If you gather data on gross domestic product

(the value of what an economy produces) for each year of independent Kazakhstan,

you will have only about 32 observations. That’s not big data, although it is

very valuable. If instead you gather survey responses by every person in Kazakhstan,

you will have more than 19 million observations. That’s big data.

It requires a shift in the way that we model

statistics. Our usual problem is to reach conclusions about the real world when

we know only a little bit about it. For example, we may want to know whether

the typical Kazakhstani approves of President Kassym Jomart Tokayev. But we

have enough money only to survey 100 people. Can we extrapolate our results to the

nation? Maybe, if we pick a sample so impartially that it is like a microcosm

of the nation. “Inferential testing” determines when this is the case, and it

usually eats up half of a course on econometrics (the economist’s term for

applied statistics). But if we can survey every Kazakhstani, our usual problem

disappears. Even if we can survey “only” a million Kazakhstanis, inferential

testing will go the way of the dodo. If randomly sampled, a million observations can give us an accurate picture of the nation.

But big data are not a panacea. They cannot substitute for clear thought. For example, even if we survey every Kazakhstani, we will get nonsense from regressing the respondent's opinion of Tokayev upon the respondent's blood type.

A more subtle problem is the failure to control for factors that relate to the explanatory variable that interests us. For example, in the Mincer equation, we may regress the (natural log of) the wage on education across workers: Wage(i) + a + b*Number_of_years_of_schooling(i)+..., where i indexes the worker. Our estimate of the coefficient b gives the rate of return to another year of education. But the model is not as perfect as it may seem. Talent also affects the wage: Talented people are highly productive. And talent correlates with education: Talented people earn advanced degrees. But there is no obvious way to measure talent: IQ is but a crude gauge. So we cannot control for talent in the Mincer equation. Since it does rise with education, part of the rate of return that we ascribe to schooling is really due to talent. That is, we will overestimate the rate of return to education. This problem will persist even if we have a zillion observations.

Finally, big data are a headache to manage. We need a way to find particular facts quickly in a dataset of millions of observations, and to identify fake or misleading data. This may require new theories of computer science and statistics. Whether these can be developed in a doctoral program aimed at political science students still struggling with the multiplication tables is, well, food for thought.

I don’t mean to suggest that Dr. Gainous would be wholly

useless. Academic deans are often appendages

anyway, and one like Dr. Gainous may have entertainment value. The problem is

to determine his fair salary. May I recommend consulting the pay schedule at

Barnum & Bailey? – Leon Taylor, Seymour, Indiana tayloralmaty@gmail.com

Notes

For useful comments, I thank but do not implicate Mark Kennet.