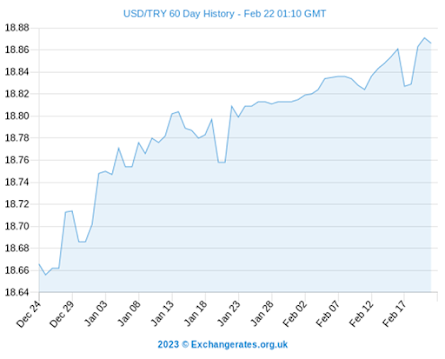

The February 6 earthquakes threw financial markets

into chaos in Turkey. They undermined demand for the Turkish currency, the lira,

weakening its dollar value. Turks holding

lira became poorer in dollars. They couldn’t afford to buy many things from other countries.

But at least Turkey has a technically competent

central bank, which manages the supply of lira. The President of Turkey, Recep

Tayyip Erdogan, just won’t let the bank do its job, that’s all.

Now consider neighboring Syria, which also suffered

from the 7.8-magnitude earthquakes as well as from a 6.3-magnitude aftershock

on the border February 20. Far from

having technical prowess, the Central Bank of Syria doesn’t even have a Web

site that works. In 2020, the United States

Treasury sanctioned the Bank for its “deep banking ties” to a sponsor of

terrorism, Iran, choking off its dollars.

Without dollars, the Bank cannot back up the value of the

Syrian pound. The pound slid against the dollar throughout late 2022, plunging

to its record low of 6,850 pounds in late December, despite the central bank’s

attempt to fix the exchange rate at 3,015 pounds on December 6. Back in 2011, before the civil war, 47 pounds

had traded for a dollar. Thus the dollar value

of the Syrian pound had fallen 99.3%. It

was virtually worthless. The average monthly Syrian income, of 130,000 pounds, came to less than $19. Average annual income, expressed in dollars, had

fallen by nearly 92% since 2010, according to my calculations (see the Notes).

And this was weeks before the earthquakes. As in Turkey, the decimation of homes and

roads will sharpen the demand for hard-to-find shelter and food. Prices will skyrocket. Inflation in Syria was 139% in 2020, if you

can believe Trading Economics, which does not explain its methods. The Syrian pound can no longer buy many goods;

Syrians who saved pounds will find them more useless than ever. People will lose their homes and starve.

But now Syria’s story diverges from Turkey’s -- in a way that it hadn't before the civil war broke out in 2011. At that time, Syrian President Bashar al-Asad had looked like the reformist son of the repressive late ruler, a young, Western-trained eye doctor who would modernize his homeland. The economy was growing 3% or 4% per year -- not great but not bad -- and inflation was only about 4%.

Arab Spring, Syrian Storm

But pro-democratic protests, stemming from the Arab Spring in the region, exposed the delusion in those dreams. At first, Asad made concessions, such as repealing a law that permitted arrests without charges. But when protesters proliferated, he ordered his troops to attack them. So began the war. It has killed more than 300,000, according to United Nations estimates -- and by some media reports more than half a million. It has also deprived millions of their homes.

Turkey can hope for dollars from the West. Syria cannot. Its President is waging a war that the West abhors and sanctions: In 2012, 130 countries recognized the opposition Syrian National Coalition. Asad's main support is from the Kremlin. With friends like that....

On top of it all, the central bank of the US, the Federal Reserve, has just cut off the supply of dollars to Iraq, which had sold them to Syria, because of laundering under the table. The central bank of Syria is up the creek, and the crocodiles are circling.

With dollars, Turkey can steady the lira and stanch the loss of value from lira savings. But humanitarian aid is the most that Syria can expect. With no dollars and no credibility, its central bank can do nothing about the incredible shrinking pound.

This means that imports from other countries are becoming more expensive. Since Syrians appear to import far more than they export, life is becoming prohibitively costly for them. Even if the central bank can put its hands on a few dollars, just possibly with Russian connivance, it will probably use them to pay down the government's foreign debt, which the CIA estimated at 95% of gross domestic product in 2017.

The refugees are thick in Idlib Province, in rebel-held, war-torn northwest Syria, west of Aleppo, the second largest city in Syria (Damascus is largest). See Figure 1. They live in tents and on humanitarian aid already stretched to the breaking point. The United States provides $185 million in aid in all to Syria and Turkey for the earthquakes.

Figure 1: Syria and surrounding countries

Figure 2: Rescuers comb rubble in the town of Hamen, in Idlib province, after earthquakes

Source: Al-Jazeera

It's hard to find good data on Syria. The World Bank does not report consumer inflation for any year since 2012, when the civil war began. The IMF Datamapper reports no economic data for Syria, period, since 2010. But I crudely and foolhardily calculate that annualized inflation in late December may have hit 110% (see the Notes). It’s undoubtedly higher today. History repeats like a crone, and the Syrians are getting wiped out once again. --Leon Taylor, Baltimore tayloralmaty@gmail.com

Notes

The IMF Datamapper reports 2010 income per capita, expressed

in dollars using the exchange rate at that time, as $2,810. In December 2022,

average monthly wages expressed in dollars were $19. Times 12 gives us $228, an

implied loss of income of 91.9%.

By the quantity equation of exchange, dP/P = dM/M + dV/V

– dQ/Q, where P is the price level, M is the money supply, V is velocity (crudely,

the rate at which we spend money), and Q is output. The equation says the inflation

rate equals the growth rate of the money supply plus the growth rate of

velocity minus the economic growth rate.

We have good data on none of these variables.

I assume that spending habits have fixed velocity this

year, so dV/V = 0. Average income has fallen 91.9% since 2010, indicating a

linearized annual rate of decrease of -91.9 / 12 = -7.6%.

Finally, I assume that the loss of dollar purchasing

power in the Syrian pound is due to inflation of the money supply. The loss rate of dollar purchasing power from

December 6 to December 28 was 56% if we assume that the dollar was worth 3,015

Syrian pounds when the central bank set that official exchange rate. The

annualized loss rate implied is virtually 100%. So far, the implied rate of

inflation is 107.6%.

Finally, the GDP growth rate is the growth rate of average

income plus the growth rate of the population. The Syrian population was 21.4

million in 2010. The civil war killed roughly a half million and sent 6.7

million fleeing to other countries. The implied rate of decrease in the

population from 2010 to 2022 was 33.4%, or a linearized annual rate of 2.8%.

In sum, the implied rate of inflation is 107.6% + 2.8%

= 110.4%. This is probably an underestimate.

I use a linearized rate of change for income and population, rather than an exponential rate, because the changes, especially in income, are pretty extreme. The exponential rate of change assumes that the actual rates of change decrease over time: That is, the rate of change in the rate of change is falling. I believe that in reality the rate of change in the rate of change was either constant or increasing. The use of a linearized rate of change is conservative in assuming a constant rate of change in the rate of change.

References

Al Jazeera. Photos: Deadly quake intensifies suffering of displace Syrians. February 6, 2023. Photos: Deadly quake intensifies suffering of displaced Syrians | Earthquakes News | Al Jazeera

Arab News. Syrian

pound hits new low on black market amid fuel crisis. December 11, 2022. Syrian pound hits

new low on black market amid fuel crisis | Arab News

ARK News. The

Syrian pound continues to decline.

December 28, 2022. The Syrian pound continues to

decline | ARK News

International Monetary Fund. Datamapper. IMF DataMapper

Rick Noack and Aaron

Steckelberg. What Trump just triggered in Syria, visualized. Washington Post. October 17, 2019.

US Central Intelligence Agency. World Factbook. Syria - The World Factbook (cia.gov)

US State Department. US assistance to emergency earthquake response efforts in Türkiye and Syria. February 19, 2023. U.S. Assistance to Emergency Earthquake Response Efforts in Türkiye and Syria - United States Department of State

US Treasury Department. Treasury targets Syrian regime

officials and the Central Bank of Syria.

Press release. December 22, 2020. Treasury Targets

Syrian Regime Officials and the Central Bank of Syria | U.S. Department of the

Treasury