Matt Gaetz: The dark prince of debt? Photo:

AP

Copyright: 2019 CQ-Roll Call, Inc.

Despite some progress in talks between Congress and the White House, default on the United States government debt rears its

greedy head, thanks to hardliners like Representative Matt Gaetz (R-Florida). “Gaslighting nearly $50 trillion in debt to

America is something my conscious cannot abide at this time,” he declares

in a press release. The Congressman’s conscience

and spelling are worthy of study.

Meanwhile, one may easily think that we should avoid future default crises

by doing away with debt limits entirely.

But this cure may aggravate the disease.

Excessive government debt is not a figment of the

Republican imagination, as overactive as it is. Figure 1 shows that debt’s

share of the economy has been rising since the administrations of President Ronald

Reagan. It accelerated through the administrations of Barack Obama and, ah yes,

Donald Trump. GOP bluster notwithstanding, it has fallen since Joe Biden took

over in 2021.

The debt share rises in most recessions, shown by the

shaded columns in the figure. That’s predictable. To fight rising unemployment, governments borrow to spend more, which adds

to debt. But after the recession, the debt usually keeps rising. Does debt

addict?

Figure 1: The ratio of federal government debt to gross domestic product

Like fentanyl aficionados, governments can’t always help

themselves. Politicians buy your vote by

offering you what you want, free of charge. They will gladly make our

grandchildren pay, since the kids don’t vote today. Spend now, tax much later. For example, conservatives may seek to cut

taxes to the rich today, in exchange for their support. This tax cut may

produce a deficit today: We spend more than we can immediately pay, so we must

borrow. Future taxpayers get stuck with

the bill.

Conservatives are not alone in yielding to temptation.

Consider Social Security. Today’s

workers pay for today’s retirees. In effect, tomorrow’s retirees finance today’s.

But Social Security is politically untouchable: Retirees object more fiercely to

cuts in benefits than workers do to increases in the Social Security tax. This is partly because the worker thinks that

she will get the tax hike back later in pension benefits, that by paying the

tax she is just saving for herself. Wrong.

She won’t see that money again.

If Congressmen gain from shifting Social Security costs forward, then the share of Social Security spending in the economy should rise over time. Figure 2 is from Social Security's annual report for 2017. From 1975 to 2017, across age groups, the share tends to rise. In 1996, Congress passed legislation to curb Social Security spending, but it succeeded only until 2007. Of course, the program's share of the economy depends on growth in the number of recipients and in the economy. Controlling for the average payment, if the number of recipients rises faster than GDP, the share will rise. But Congress should take this into account.

Figure 2: Social Security spending as a share of gross domestic product

Source: Social Security AdministrationCongressmen may also spend more than we can afford

because they can ignore us. Two Representatives on an appropriations committee

may swap votes to approve their respective pork barrels, fobbing off the cost

onto a Congress unlikely to object to their small deal. But many small deals

add up to a big deal.

The bureaucracy too may press for spending. To bolster

its salaries, it has reason to inflate its estimates of service costs. In the 1940s,

a mule-headed Senator from Missouri, Harry Truman, made a name for himself by

exposing military waste. As late as the 1980s,

Senator William Proxmire (D-Wisconsin) became famous, or more accurately

infamous, for his Golden Fleece award for research grants that seemed

frivolous. Today, the Congressional road to fame descends through the burgs of

invective. Never mind about cunning

departments. Democrats eat babies, that’s the problem.

We are heading for default not because of a debt limit

per se. The problem is that the debt limit we now have makes no sense,

because it does not recognize that as the nation becomes richer, it can afford

to borrow more. It is as if we limit a billionaire to the same $1,000 credit-card

limit as applies to a high school student.

We should adjust the debt limit for the size of the economy by

expressing it as a share of gross domestic product, as Figure 1 does.

The foggy road

Ideally, the debt limit would just be a guideline.

Stuff happens. The government needs enough leeway to respond quickly to, say,

another pandemic. It should also recognize that debt in and of itself is not

bad. We may borrow today to study in college and earn higher income next year. And government spending does not depend only on the Congressional appetite for votes. As Figure 2 shows, the projected share of Social Security in GDP fell after 2017, because the economy seemed to grow more quickly than the number of recipients. Evidently, the forecasters doubted that Congress would take advantage of these trends to raise benefits and thus votes.

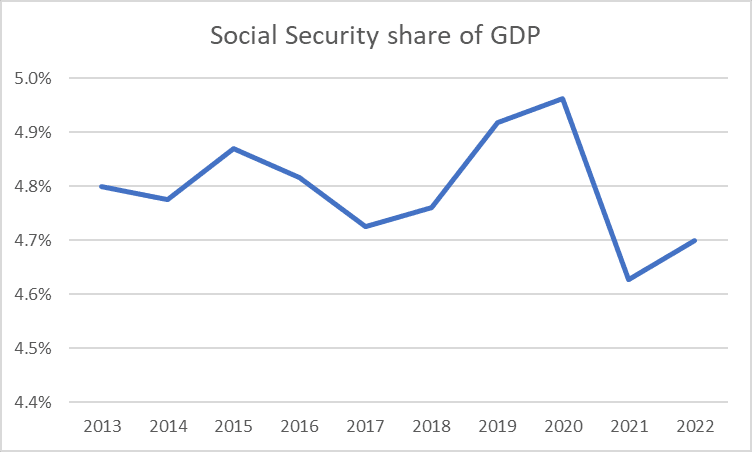

But Figure 3 shows the reality. From 2013 to 2022, the Social Security share barely changes: 4.8% at the beginning of the decade, 4.7% at the end. The spike in 2020 was probably due to the Covid-19 lockdown of the economy. At any rate, there is no evidence in these figures that Congress took advantage of favorable trends to restrain Social Security spending by much.

Figure 3: Social Security spending as a percentage share of GDP

Sources: Nominal GDP, seasonally adjusted, FRED of the St. Louis Fed; Total outgo from OASDI Trust Fund, Social Security Administration.The growing debt share is alarming, because it implies that most

government investments do not pay off in economic growth. Perhaps they pay off

in quality of life, but we don’t yet know. What we do know is that a rising

debt share implies a growing tax bite from our income. We don’t nead Gaetz, er, need Gaetz, to point that out.

--Leon Taylor, Baltimore, tayloralmaty@gmail.com

References

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. FRED Economic Data: GDP. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)

Matt Gaetz. Congressman

Gaetz Issues Statement in Response to House Debt Ceiling Vote. April 2023.

Congressman

Gaetz Issues Statement in Response to House Debt Ceiling Vote | Congressman

Matt Gaetz

Social Security Administration. 2017 annual report of the SSI program. D. Federal SSI Payments as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product (ssa.gov)

Social Security Administration. Time Series for Trust Fund Operations (ssa.gov)